Inspired by the film, director/Writer Courtney Lamb researched the history of infertility treatment in America while taking the Spring 2020 class “The Politics of Parenting” with Professor Eve Oishi at Claremont Graduate University. Melissa’s experiences were directly reflected in Courtney’s research, making it a valuable companion to the film to those interested in this fascinating and complex topic. References are listed at the end.

THE TREATMENT OF INFERTILITY IN AMERICA

Courtney Lamb | May 7, 2020

- Introduction

- Defining Infertility — Who is “Infertile”?

- Treatment Options — What Treatment is Available?

- Seeking Treatment — Why Seek Treatment?

- Consequences of Treatment — What Happens to Treatment-Seekers

- Conclusion

- References

- Notes

INTRODUCTION

How has the infertility treatment business in the United States reached its current status as a booming and even fashionable business? In order to trace the rise of this sector of the healthcare industry, we must explore the definition of infertility itself — Who is infertile? Who decides who is infertile? How is the determination that medical intervention is warranted made, and what options are available? Who decides to seek treatment? And finally, what are the consequences of the treatments for those seeking a solution to their problem of childlessness?

Infertility is common, both in the United States and in the world. On awarding the 2010 Nobel Prize in Medicine to Robert Edwards of Britain for the development of human in vitro fertilization (IVF) therapy, the Nobel Assembly noted that 10% of couples worldwide are infertile and “for many of them, this is a great disappointment and for some causes lifelong psychological trauma.” Thanks to IVF, there is an effective therapy that results in a live birth 20-30% of the time and “for many of them, this is a great disappointment and for some causes lifelong psychological trauma.” 4 million IVF babies had been born to that point.1 In the United States in 2010, about 12% of women of reproductive age saw a doctor for medical help to have a baby. Of those, 0.7% underwent an Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) treatment like IVF (Marsh and Ronner 2019, 154). There are more than 450 fertility clinics in America, and treatments are expensive — the global fertility market is projected to rise to $41 billion by 2026 (Strodel 2020).2 Today, cultural awareness of ARTs is widespread and growing, as evidenced by media reports, podcasts and books dedicated to the topic, high-profile IVF birth stories, and the inclusion of treatments in some employee benefits packages.

This paper draws on the work of sociologists, historians, physicians, journalists, political scientists, psychologists, and public policy analysts to examine the treatment of infertility in America, in the sense of both how it is defined and how it is addressed. I use this broad lens in an attempt to understand the array of social, economic, and psychological pressures that drive the decision-making of the various actors: those seeking treatment, those providing it, and those discussing and promoting it. I conclude that infertility treatment in the United States is a self-perpetuating, market-driven industry that often obscures the lived realities of those experiencing unwilling childlessness. In this way, it prevents the development of practical and realistic solutions to both private (medical and emotional) and public (social and political) contributory factors.

DEFINING INFERTILITY — WHO IS “INFERTILE”?

“Sure most women over 40 have trouble getting pregnant. But I’m not most women. I’ve scored in the 99th percentile on every standardized test I’ve ever taken.”3

Quote from Melissa Okey, who blogged about her unsuccessful attempts to get pregnant over a four year period

Who is infertile? When do they become infertile? Do they define themselves that way, or are they defined that way by others? As discussed in this section, the term and its application have a flexible history. Infertility is not a fixed, diagnosable condition. It is mutable, socially constructed, and laden with value judgements. As this paper will show, the pliability of the definition means it can be shaped to guide selected populations toward treatment.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines “infertility” as occurring to married women ages 15-49 “who are not surgically sterile, and who have had at least 12 consecutive months of unprotected sexual intercourse without becoming pregnant”. According to data from 2015-2017, 8.8% of American women fit that definition. Separately, the CDC defines “impaired fecundity” as occurring to women ages 15-49 “who are not surgically sterile, and for whom it is difficult or impossible to get pregnant or to carry a pregnancy to term”. Impaired fecundity affects 13.1% of American women.4

There are numerous implied social components to the above definitions. According to the CDC definition, only married, heterosexual couples can be counted as infertile, and either the male or female partner may be contributing to the infertility (via a low sperm count, for example, or a bicornuate uterus). Couples that do not wish to become parents would not be considered infertile, regardless of their physical ability to procreate. Thus a desire to fulfill the social role of parenthood affects the definition of infertility (Greil 2011).

Neither definition above accounts for transgender men seeking to become pregnant, or for those who are childfree by choice and thus would not report themselves as infertile. It also excludes those currently avoiding or preventing pregnancy who have never attempted to get pregnant and thus would not know if they have impaired fecundity. The CDC’s definitions overlook those whose concept of their own infertility is imposed economically or socially — for example, people who want to become pregnant but believe they cannot afford the cost of a child or cannot afford to interrupt their careers, or parents of girls whose culture primarily values boys (Davis and Loughran 2017). People who successfully use donated eggs or donated sperm or both may no longer believe they fit the definition of “impaired fecundity” because their bodies were, in practice, able to become pregnant.

Both definitions — of infertility and impaired fecundity — depend on a body-centric interpretation, which suggests that the availability of medical intervention can alter a person’s acceptance of the definition. People seeking medical intervention may refuse to claim the label “infertile.” As sociologist Ann V. Bell (2019) concluded after interviewing women who met the definition, those “situated in a medicalized context, confronted with hopeful prospects and knowledge of working body parts, are able to deny an infertile status and embrace a gendered sense of self.” Perceptions of the female fertility timeline also affect an individual’s expectation about when they should apply the labels of infertile or impaired fecundity to themselves. A study by Communications experts Robin E. Jensen, Nicole Martins, and Melissa M. Parks (2017) found that the “illness representation” of female fertility may reflect “cultural beliefs and social norms” — they found that white, highly educated American adults placed peak fertility later in the timeline, while lower income, Black, Hispanic, and LGBTQ people placed it at a younger age. This implies that the former group will be inclined to reject the label of infertility until a later age than the latter group. Both of these concepts — the rejection of the infertile label and the expanded view of the female fertility timeline — were reflected by Faith Salie, a white journalist who reported on her own experiences with egg freezing, in-vitro fertilization (IVF), and multiple pregnancies after the age of 40. Salie said, “I’ve never used the word infertility applied to my situation. To me it was always fertility treatments.”5

Those who can afford treatment and choose to seek it may do so without trying to conceive without intervention for the proscribed amount of time. Those without opposite-sex partners will seek treatment when they wish to become pregnant. Either of these groups may or may not refer to themselves as infertile.

Definitions of infertility, shaped by perceptions of who should be labeled infertile, have driven an interest in and reliance on medical interventions. In their book The Empty Cradle: Infertility in America from Colonial Times to the Present, Margaret Marsh and Wanda Ronner place the history of infertility in America in its social and temporal context. They demonstrate that even as “infertility rates have remained surprisingly consistent for more than a century,” social and cultural changes have led to a present-day reliance on and acceptance of medical intervention. In early colonial America, the female reproductive system was little understood, and white people ascribed “barrenness” to the woman only (not the couple), and the woman was personally culpable due to her physical or behavioral shortcomings (Jensen 2016, 21-27). Nonetheless, in the more communal society of that time, there was a child-inclusive social role available to childless white women, who could informally adopt a child or accept one into the household as an apprentice. By the late 18th century, the individual family was more highly prized, and the family was considered part of a private sphere. By the early 19th century, “barrenness” was reconceptualized as “sterility” and medicalized. The placement of the family in the private sphere and the medicalization of unwilling childlessness meant that responsibility for the condition passed from the community to the physician. Beginning in the mid 19th century, medical interventions became the treatment of choice, despite the low success rate and brutal, experimental nature of many of the treatments. Until recently, there has been a historically-consistent cultural pressure to fail to test men or consider their role in infertility in heterosexual couples, despite the fact that we now know that 40-50% of infertility in heterosexual couples is due to sperm problems. Meanwhile, the rise of a variety of sophisticated Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs) in the 20th century has not been accompanied by a drastically improved success rate. As Marsh and Ronner (1996, 249) write, “The principal effect of the publicity over the most advanced reproductive technologies has been not so much to report reality as to create a perception of progress. Such a perception has always been one of the key forces in encouraging the infertile to seek treatment.”

Complicating the definitions of infertility and fertility is the fact that it is not only the unwilling childless person who seeks medical intervention. The ready availability of treatments has created unofficial categories of what might be called the “hyper-fertile” (egg donors) and the “pre-infertile” (those in their 20s and 30s who harvest, freeze, and store their eggs in anticipation of future infertility). The hyper-fertile receive monetary compensation for performing reproductive labor and medically inducing their bodies to produce an excess of eggs. The pre-infertile assume an ongoing financial cost as a hedge against possible future infertility — as med student Rachel Strodel (2020) put it, she froze her eggs as a “fecundity insurance plan.” Both categories exist not just because of the treatments — IVF reportedly has a success rate of at most 35% — but because of the definitions of infertility and impaired fecundity that justify them economically and emotionally.

Thus the history of infertility of America has shaped current concepts of who is infertile, when they are declared infertile, and what they can do about it. Definitions of infertility rest on socioeconomic and cultural considerations that themselves are shaped by historical values. In the end, individuals choose to accept or reject the definitions for themselves and follow the course of action that feels right to them emotionally and fits their economic means. All of this leads to an imprecise, amorphous definition of infertility that obscures the scope of the problem and complicates the search for solutions.

TREATMENT OPTIONS — WHAT TREATMENT IS AVAILABLE?

“I’ve done 5 of these [hormone shots in the abdomen] in the past week, and, while the first one traumatized me to that point that I stared at the needle for what seemed like an hour wondering if I’d actually be able to jab myself with it, I seem to have gotten the hang of it.”6

Once someone designates themselves as “infertile,” what treatment choices are available to them? This section traces the history of infertility treatments in America and uncovers how the medicalization of the problem turned physicians into infertility entrepreneurs, enabled by a lack of patient-focussed regulation or legislation.

Marsh and Ronner’s The Empty Cradle (1996) provides a contextualized history of the medicalization of infertility treatments. Up until the mid-19th Century, an American woman desiring but failing to get pregnant would turn to prayer, behavioral modifications, and the advice of midwives. Knowledge of the reproductive system was sparse and inaccurate. By the 1850s, physicians had identified the reproductive organs as the source of infertility, and “surgery and instrumentation, rather than diet and exercise, would become the dominant therapies” (40). In the next few decades, physician J Marion Sims invented pioneering gynecological instruments and surgical techniques while attempting to correct presumably malfunctioning and malformed reproductive organs. This focus on mechanical solutions absolved patients of blame for their condition, but also removed their agency (Jensen 2016, 28-24). He and his colleagues perfected their techniques through trial-and-error surgeries and procedures performed without anesthesia mostly on enslaved women and poor and working class immigrants (Marsh and Ronner 1996, 64-66).7 The physicians considered surgery a success if the patient survived — no data was kept on whether they remained healthy or successfully conceived (Sims “left behind no quantitative data to confirm his confidence in his procedures,” 63).

This was the beginning of the medicalization of treatment and established a common thread throughout the history of American infertility treatments: the bodies of those defined as infertile used as testing grounds for largely unregulated, unbounded, poorly verified, and minutely invasive procedures. As discussed later in this paper, patients today expect to suffer from their treatments and often welcome prolonged suffering as proof of how hard they are working to have a baby.

From 1870-1900 physicians (who were almost all male) were still generally unable to cure what was then labeled “sterility”, unwilling to consider the role that men and inadequate sperm played, and unsure of how embryos were created. Therefore, they concentrated on dictating women’s behavior (76). Since the fertility rate was lowest among urban native-born whites and highest among immigrants and black women, white women were urged to conserve their energy in order to power their wombs (Jensen 2016, 49-56). Education, work, and activism were branded the enemy of fertility, conflating sexism with infertility — for example, Dr Edward H. Clarke’s popular and influential 1884 book Sex in Education; or, A Fair Chance for the Girls argued that higher education caused nervous collapse in females (Tsang 2015, 138-142). In the early 20th Century, scientists discovered the mechanics of menstruation and ovulation and developed reproductive endocrinology (Marsh and Ronner 1996, 134-148). Despite the fact that more medical treatments (e.g. insufflation of fallopian tubes, tuboplasty) were now available, and more women’s bodies were subjected to these treatments, there was no proven increase in live births (160). The post-World War II era saw the introduction of dedicated fertility clinics, despite the lack of data proving success of the treatments (170).8 The desire to fulfill the expected role of maternal homemaker during the Baby Boom era and a flourishing belief in the miracles of science proven by wartime technical and engineering successes encouraged infertile women to seek any treatment available.

The succeeding decades brought on a steady cascade of medical advances in reproductive technologies, as detailed in In-Vitro Fertilization: The Pioneer’s History (2018) by physicians and editors Gabor Kovacs, Peter R Brindsen, and Alan H DeCherney. The early 1960s saw the introduction of synthetic hormones to induce ovulation. In the next two decades, the introduction of new ARTs, amniocentesis, legalized abortion, and female birth control (The Pill) came to a head at once, along with social equality movements like Women’s Rights and Civil Rights and the profound political upheavals and looming threats of the Cold War, Watergate, the Thalidomide disaster, and environmental threats (such as those enumerated in the 1962 book Silent Spring) that inaugurated Earth Day and environmental activism. Social instability and a general lack of trust in authority created conditions that made both fertile and infertile bodies a matter of heated national debate. Women with careers chose to wait until their 30s to give birth, making age and fertility a topic of debate for the first time. The first IVF baby was born in England in 1978, leading the Vatican to subsequently denounce IVF as threatening life by destroying embryos. A technique to insert sperm directly into eggs promised a cure for male-factor infertility in 1992. Fertility clinics proliferated in the 1990s, leading Congress to pass the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act in 1992, creating a clinic-specific (with purely voluntary participation) data registry. Congress appointed a Human Embryo Research Panel in 1995, which remains in place despite an Amendment that restricts the use of federal funds for research with human embryos. A breakthrough in egg freezing technology in 2009 made embryo selection possible, reducing the possibility of unintended multiple births. There are even more innovations on the horizon, including stem cell technology that would manufacture egg and sperm cells from skin cells, perhaps making egg and sperm donation obsolete (Mundy 2019).

All of these advancements have taken place despite (or because of) an overall lack of regulation or oversight of the fertility industry in America. As Marsh and Ronner put it, “Every other developed nation has addressed the medical and ethical issues surrounding these advanced reproductive technologies by creating national policies and regulations and by periodically revising those policies. The United States has not” (2019, 7). They trace this back to the 1973 Roe decision that legalized abortion and inadvertently launched a powerful, adversarial Right to Life movement that, in line with the Vatican, argues that destroying an embryo is equivalent to murder. This created an enduring political environment in which legislators were unable or unwilling to use federal or state resources to pursue the science of reproduction and ARTs. As a consequence, the people seeking those services must rely mostly on private industry. The professionalization of the infertility industry led to the early-1980s establishment of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART), an umbrella organization for American fertility clinics that acts as a data clearinghouse and source of best practices, but SART has no enforcement or regulatory powers, and membership and data sharing are both optional.9

Additionally, the United States’s marketplace approach to healthcare dictates both that for-profit private industry will drive treatment choices and that infertility must be defined as a medical condition (as opposed to an “unfulfilled desire”) in order to be addressed by society in the form of insurance coverage and scientific research. As historians Gayle Davis and Tracey Loughran write in their 2017 book The Palgrave Handbook of Infertility in History : Approaches, Contexts and Perspectives, “the elision of infertility (as a lived experience) with ARTs (a technological ‘solution’ to a medical condition) risks neglecting both the much longer history of the condition, and the diverse experiences of those who have experienced involuntary childlessness outside highly medicalized contexts” (3). Legislators, in the form of a Republican-controlled Senate and White House in the late 1990s and early 2000s, codified ARTs around consumer protection, further associating infertility with consumerism and incentivizing higher costs of treatment.10 This focus diverted political and activist attention away from the social and economic contributory factors of infertility and absolved the government from the responsibility of addressing them; they include the lack of: mandatory, paid workplace maternity leave, affordable healthcare, state-funded preschools, or equitable pay (Solinger 2013, Marsh and Ronner 2019).

As a result, Americans facing impaired fecundity may currently choose from a variety of highly medicalized and expensive treatments of escalating intensity and unknown risk, including egg freezing, IUI, IVF, egg and/or sperm donation, and surrogacy.11 Each of these involves injections and suppositories delivering multiple drugs to the treatment-seeker’s body over many months, sometimes over years, in fluctuating cycles that may be interrupted by emotionally and physically traumatic miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, abortions of unviable fetuses, or stillbirths. The long-term risks of prolonged use and withdraw of fertility drugs is understudied and unknown (Solinger 2013, 103). The long-term psychological risks have rarely been considered in scholarship or in popular debate.12

SEEKING TREATMENT — WHY SEEK TREATMENT?

“The real problem with the waiting and the money and the shots is that really we’re just gambling…And the odds are terrible. Worse than roulette. Like a roulette wheel if it was 85% green double zeroes.”13

Once a person accepts the designation as infertile or pre-infertile and becomes aware of the available treatment options, what makes them decide or decline to seek treatment? In this section, I discuss the powerful cultural influences that emphasized individual responsibility (and blame) for unwilling childlessness. In this way, they stratified treatment by guiding some people toward ARTs while implicitly discouraging equitable social or political solutions.

The proliferation of medical treatments for infertility has occurred in the conspicuous absence of reliable data that can accurately predict the outcome of any given cycle of any given treatment, which is compounded by the complex array of cofactors (such as egg age and viability, previous births, and health history) affecting that outcome on a patient-by-patient basis. Most fertility problems result from medical circumstances or socioeconomic factors such as a lack of access to health care and health education, and living in proximity to hazardous industrial sites; most infertility is due to blocked fallopian tubes, endometriosis, male infertility, effects of sexually-transmitted diseases, polyps, polycystic ovary syndrome, environmental toxins, or some combination thereof (Solinger 2013, Twenge 2013). Yet people experiencing “impaired fecundity” but who may or may not have trouble conceiving through regular sexual intercourse also seek out fertility treatments. This means that self-reported data from fertility clinics includes same-sex couples, transgender people, people using younger donor eggs, and “single mothers by choice” (or SMBC, a phrase coined by Jane Mattes (1994), founder of an organization of the same name). In addition, studies have shown that black IVF patients have double the rate of miscarriage of white patients, and that live birth rates from IVF are significantly lower for (in order) black, Asian, and Hispanic women as compared to white women. There’s no explanation as to why this is (Strodel 2020). Clinic success rates therefore must be scrutinized by multiple subcategories in order for any one patient to determine their own likelihood of success, a task so daunting as to be impractical.

As discussed earlier in this paper, this lack of quality data has been a constant throughout American history going back to the earliest (and least bound by ethics) pioneers of medical gynecological interventions. An influential New England Journal of Medicine article by physician Alan DeCherney and professor Gertrud Berkowitz titled “Female Fecundity and Age” raised the alarm about a precipitous drop in artificial insemination success rates for women over 35. In their review of a study of 2193 French women (Schwartz and Mayaux, 1982), the authors caution about unknown qualifying factors yet make sweeping suggestions that reveal their assumptions about women’s behavior: “Perhaps the third decade should be devoted to childbearing and the fourth to career development” (425). Decades later, psychology professor Jean Twenge (2013) reviewed the sources and data of influential age-focussed studies like that one and concluded that fertility does decline with age but huge drops do not occur until age 40, and that timing sex for the most fertile part of the cycle can erase the age difference.

But in the meantime, cultural assumptions about age and fertility overwhelmed any dispassionate interpretation of the (paltry and inconclusive) data. As discussed below, Twenge’s refutation has done little to change the conversation — or the industry — around age and fertility, which was supported by a historical association of infertility with notions of time. The medicalization of treatment beginning in the early 20th century created the impression that physicians and scientists could track clinical time and intervene at specific moments in order to “align infertile women within ‘normal’ temporal perimeters and thereby induce fertility.” A woman’s “embodied sense of timing and reproduction” was “characterized as, at best, trivial, and, at worst, meaningless.” (Jensen 2016, 151).

In addition, the Women’s Movement of the 1970s spurred a powerful backlash that fueled anxiety around the fecundity of liberated women. Richard Cohen popularized the term “biological clock” as applied to “career women” in a 1978 Washington Post article in which he declared, “There was something about their situation that showed, more or less, that this is where liberation ends.”14 A June 2, 1986 Newsweek cover article entitled “The Marriage Crunch” caused a panic by sensationally claiming that women over 40 are more likely to be killed by a terrorist than to find a husband (never mind that the article was based on a subsequently thoroughly debunked unpublished article (Garber 2016, Zaslow 2006)).15 The American Society for Reproductive Medicine garnered invaluable free media exposure for their provocative 2001 ad campaign warning about “Advancing Age” and featuring an hourglass fashioned from a rapidly-depleting baby bottle — their President noted that “the National Organization for Women was helpful in spreading our message far and wide. Without their negative reaction, most women of reproductive age would never have heard of our medical message” (Soules 2003). An April 15, 2002 Time cover story “Babies vs. Career” (Gibbs 2002) continued to frame women’s lives as a battle between oppositional desires, drawing publicity to economist Sylvia Ann Hewlett’s 2002 book Creating a Life: Professional Women and the Quest for Children, which made it clear that she believed women should not even try to “have it all.” New York Magazine’s May 20, 2020 article “Baby Panic” described the effect of Hewlett’s warnings on 20- and 30-something New Yorkers, who were convinced that their lifestyle and career choices were dooming them to future infertility. Infertility supplanted the supposed “overpopulation crisis” of the 1970s and 1980s as the greatest perceived threat to social stability (Marsh and Ronner 1996).

By the early 21st century, social anxieties about female fecundity collided with the prolific scientific advancement of ARTs to normalize the pursuit of assisted reproduction. Prominent figures like Michelle Obama, Thomas Beatie (the transgender “Pregnant Man”), Sen Tammy Duckworth, and Amy Schumer went public with their IVF stories. Media like Molly Hawkey’s SMBC podcast Spermcast16, the Eggology Club podcast (“redefining the modern day journey to parenthood”), and FertilityIQ.com served a robust and potentially lucrative subculture around fertility treatments, which also includes fertility clinic seminars and conferences, fertility-specific vitamins and supplements, OTC testing kits, and apps like Flo Period Tracker and Ovulation and Clue Period & Cycle Tracker.

Business took note of the boutique medicalization of infertility. According to a survey by FertilityIQ.com, as of 2020 more than 400 American businesses offered employee benefits covering some portion of the cost of IVF treatment.17 Tech companies like Google, Facebook, and Apple took the lead, luring recruits by covering the cost of egg freezing.18 Venture capitalists and hedge funds poured money into the booming fertility business, including dedicated egg-retrieval and storage businesses (Strodel 2020, Mundy 2019). As journalist Liza Mundy put it, “What egg freezing is…is one more paid-subscription service, like Netflix or Zipcar” (2019). She questions whether there will be a future backlash due to the failure of frozen eggs to produce live births; medical student Rachel Strodel, who had her own eggs frozen, shares similar concerns (2020). Strodel calls for an independent government body to regulate the industry due to “urgent inequities, unfounded promises and disregard for medical best practices in the field.”

CONSEQUENCES OF TREATMENT — WHAT HAPPENS TO TREATMENT-SEEKERS?

“I am sad. I am sad the way I have been sad every month for the last 2 years. The only difference is this time I had 5 office visits, 3 transvaginal ultrasounds, 3 blood samples, 6 self-administered injections, and 12 progesterone suppositories leading up to the sad, and the news came in a phone call instead of in menstrual cramps and blood.”19

As we’ve seen, due to a dearth of reliable and standardized data, the definition of the infertile population and the selection of treatment seekers is largely determined socially and culturally. Treatment is almost entirely centered on medical technology. Success is marked by live births, which occur for only a minority of patients, and may only happen after many rounds and years of expensive treatment. Not included in these calculations is the multivariant cost of this method of designating infertility and seeking treatment — costs that accrue in terms of money, time, job and career advancement, and intense physical and emotional consequences.

Mundy and Strodel are sounding the alarm over a prime consequence of the centering of ARTs by the medical industry and by employers and employees: egg freezing and IVF is mistakenly considered a “cure” for infertility despite low success rates. The existence of fertility loan firms, often promoted by fertility clinics or physicians, “sets up powerful incentives to encourage medical intervention regardless of the prognosis for success” (Hagel 2013). Cultural prejudices and assumptions about age and fertility have primed what I’ve termed “pre-infertile” people to accept ongoing personal responsibility for decisions they are being urged to make (even scared into making) around their fecundity. Employers and insurance will assist them in taking personal responsibility — and blame — by providing costly benefits and services, which further fuels the fertility industry. Fertility businesses offer an array of fertility services, often in consumer-friendly packages with discounts and deals.20 In all instances, people facing unwilling childlessness are embraced as consumers while being rejected as community members who deserve policies and legislation that integrates them into society and the workforce without punishing or stigmatizing them via lower wages, stunted career paths, and enormous financial burdens from treatment and egg storage.

The elision of consumerism with infertility also determines who seeks treatment. There is no scientific consensus on what the female fertility timeline is, so the fact that white and higher-educated people believe they reach peak fertility later in life means they are more likely to seek infertility treatment (Jensen 2018). Sociologist Ann V. Bell found that, due to their access to and comfort with medical intervention, a diagnosis of infertility is the beginning of hope and the removal of blame for higher class women. Lower class women, by contrast, assigned alternate, often fatalistic, explanations for their diagnosis, including self-blame, heredity, and environmental toxins (Bell 2014). This confirms historian Elaine Tyler May’s finding that “many [childless people who wrote to her] believe that parenthood is a status that can be chosen but must also be deserved” — and they expressed an expectation that medical institutions would help them (1995, 6). Either way, the result is that people grappling with unwilling childlessness are saddled with psychological, economic, and physical burdens.

Technological innovations spurred by financial incentives and consumer/patient demand have enabled monitoring and medical intervention at every possible stage of preconception, conception, and pregnancy — including home pregnancy tests, basal temperature thermometers, spermcheck kits, hormone pills, injections, and suppositories, vaginal and pelvic ultrasounds, amniocentesis, blood and urine tests for pregnancy-related markers, ovarian stimulation, and egg harvesting. As Lita Linzer Schwartz (1991) notes, the mechanization of the process and the monitoring of every step leads to a self-identity of “success” or “failure” at each stage of uterine change and embryo growth, implantation, and development. Schwartz (a psychologist) warns about the psychological consequences of this. Whereas a non-monitored, unassisted pregnancy may result in a very early, unnoticed miscarriage that leaves no psychological scar, the smallest bodily changes become cause for celebration or grief to a person paying for ARTs. By continually keeping score, the treatment-seeker is incentivized via a “technological mandate” (Jensen 2016, 6) to continue until they “win,” no matter the cost — the process keeps “sufferers suspended in a state of hope” (Davis and Loughran 2017, 3). They compound their dismay at infertility — their “fertility-specific distress” (Greil et al. 2011) — with trauma caused by the treatment itself. This occurs despite the fact that those who can afford ARTs often describe it as empowering — Faith Salie (2010) declared that “the option to freeze her eggs is just about the most empowering choice a single woman who knows she wants to be a mother can make.” Yet it is empowerment built on a conception of the non-reproducing body as defective (Loughran 2018) and on the physical suffering caused by the treatments as proof of having earned the right to parenthood. English professor Sally Bishop Shigley described that conundrum and her unsuccessful IVF treatments this way: “Thinking that you could have controlled the outcome and did not is much worse than thinking that the infertility is a natural anomaly or fate” (in Davis and Loughran 2017, 43).

By tethering a desire for children to medical interventions, American society demands that infertile and even pre-infertile people identify as failures with unacceptable bodies. It therefore demands that they incur many layers of cost that affects their physical and mental health and their functioning in society but remains mostly unacknowledged and unaddressed by society at large.

CONCLUSION

“I didn’t want to pay such a high price for my meandering, follow your dreams, take time and explore the world life path that brought me to this point.”21

Due to an incomplete and subjective definition, the medicalization of treatment, and market-driven healthcare, Americans experiencing unwilling childlessness are driven to perpetuate and enhance the existing for-profit, largely unregulated treatment industry, leaving no room for competing solutions.

As more people share their stories of unwilling childlessness and the costs and consequences of medical interventions, criticism and questioning of the process will be crucial to effecting positive change. It will be necessary to make the private even more public in order to address the reality of infertility in an equitable, compassionate, economically-sound, and efficacious manner.

REFERENCES

Bell, A.V. (2014), Diagnostic diversity: The role of social class in diagnostic experiences of infertility. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36: 516-530. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12083

Bell, Ann V. “‘I’m Not Really 100% a Woman If I Can’t Have a Kid’: Infertility and the Intersection of Gender, Identity, and the Body.” Gender & Society 33, no. 4 (August 2019): 629–51. doi:10.1177/0891243219849526.

Davis, Gayle, and Tracey Loughran, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Infertility in History : Approaches, Contexts and Perspectives. Palgrave Handbooks. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52080-7.

DeCherney AH, and Berkowitz GS. “Female Fecundity and Age.” The New England Journal of Medicine 306, no. 7 (1982): 424–26.

Eggs.Com. Anonymous Columbia Broadcasting System, 1999. https://video-alexanderstreet-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/watch/eggs-com.

Garber, Megan. “When Newsweek ‘Struck Terror in the Hearts of Single Women’.” The Atlantic. June 2, 2016. Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/06/more-likely-to-be-killed-by-a-terrorist-than-to-get-married/485171/.

Gibbs, Nancy. “Making Time For a Baby.” Time. April 15, 2002. Accessed April 22, 2020. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1002217,00.html.

Greil, Arthur, Julia McQuillan, and Kathleen Slauson-Blevins. “The Social Construction of Infertility: The Social Construction of Infertility.” Sociology Compass 5, no. 8 (2011): 736–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00397.x.

Greil, Arthur, Karina M. Shreffler, Lone Schmidt and Julia McQuillan. “Variation in distress among women with infertility: evidence from a population-based sample.” Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 26, no. 8 (2011): 2101–2112. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der148

Hagel, Alisa. 2013. “Banking on Infertility: Medical Ethics and the Marketing of Fertility Loans.” Hastings Center Report 43 (6): 15–17. doi:10.1002/hast.228.

Jensen, Robin E. Infertility : Tracing the History of a Transformative Term. The Rsa Series in Transdisciplinary Rhetoric. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

Jensen, Robin E.1, r.e.jensen@utah.edu, Nicole2 Martins, and Melissa M.1 Parks. 2018. “Public Perception of Female Fertility: Initial Fertility, Peak Fertility, and Age-Related Infertility Among U.S. Adults.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 47 (5): 1507–16. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1197-4.

Kovacs, Gabor, Peter R Brinsden, and Alan H DeCherney, eds. In-Vitro Fertilization : The Pioneers’ History. Cambridge Medicine. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

— Chapter 8 – The Development of In-Vitro Fertilization in North America After the Joneses

Loughran, Tracey. “Infertility through the ages—and how IVF changed the way we think about it.” The Conversation. May 1, 2018. Retrieved Feb 14, 2020. https://theconversation.com/infertility-through-the-ages-and-how-ivf-changed-the-way-we-think-about-it-87128

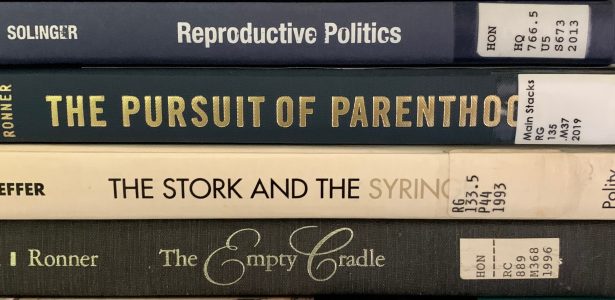

Marsh, Margaret S, and Wanda Ronner. The Empty Cradle : Infertility in America from Colonial Times to the Present. The Henry E. Sigerist Series in the History of Medicine. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Marsh, Margaret S, and Wanda Ronner. The Pursuit of Parenthood : Reproductive Technology from Test-Tube Babies to Uterus Transplants. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019.

Mattes, Jane. Single Mothers by Choice : A Guidebook for Single Women Who Are Considering or Have Chosen Motherhood. 1st ed. New York: Times Books, 1994.

May, Elaine Tyler. Barren in the Promised Land : Childless Americans and the Pursuit of Happiness. New York: BasicBooks, 1995.

Mundy, Liza. “Pausing Fertility: What Will Happen When the Eggs Thaw?” Scientific American. May 1, 2019. Accessed Feb 21, 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/pausing-fertility-what-will-happen-when-the-eggs-thaw/

Okey, Melissa. In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (blog). https://melissaokey.wordpress.com.

“Opinion: Faith Salie in Vitro.” Columbia Broadcasting System, 2010. https://video-alexanderstreet-com.ccl.idm.oclc.org/watch/opinion-faith-salie-in-vitro.

Schwartz, D, and M. J Mayaux. “Female Fecundity As a Function of Age: Results of Artificial Insemination in 2193 Nulliparous Women with Azoospermic Husbands.” Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 37, no. 8 (1982): 548–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006254-198208000-00019.

Schwartz, Lita Linzer. Alternatives to Infertility Is Surrogacy the Answer? Frontiers in Couples and Family Therapy, 4. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1991.

Solinger, Rickie. Reproductive Politics : What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Soules, Michael R. “The story behind the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s prevention of infertility campaign.” Fertility and Sterility, Volume 80, Issue 2 (August 2003): 295 – 299.

Stabile, Bonnie1, bstabile@gmu.edu. “Reproductive Policy and the Social Construction of Motherhood.” Politics & the Life Sciences 35, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 18–29. doi:10.1017/pls.2016.15.

Strodel, Rachel. “Fertility clinics are being taken over by for-profit companies selling false hope.” NBCNews.com. March 1, 2020. Accessed March 1, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/fertility-clinics-are-being-taken-over-profit-companies-selling-false-ncna1145671.

Thorpe, JR. “How Infertility Was Talked About Throughout History — Because to Fight a Taboo, You Need to Understand Its Origins.” Bustle.com. Apr 14, 2015. Accessed Feb 14, 2020. https://www.bustle.com/articles/76161-how-infertility-was-talked-about-throughout-history-because-to-fight-a-taboo-you-need-to

Tsang, Tiffany Lee. “‘a Fair Chance for the Girls’: Discourse on Women’s Health and Higher Education in Late Nineteenth Century America.” American Educational History Journal 42, no. 2 (2015): 137–50.

Twenge, Jean M. “How Long Can You Wait to Have a Baby?” The Atlantic. July/August 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/07/how-long-can-you-wait-to-have-a-baby/309374/.

Zaslow, Jeffrey. “An Iconic Report 20 Years Later: Many of Those Women Married After All.” The Wall Street Journal. May 25, 2006. Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB114852403706762691.

NOTES

1 “Press release.” NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2020. October 4, 2010. Accessed March 30 2020. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2010/press-release/>.

2 Strodel references Data Bridge Market Research, “Global Fertility Services Market — Industry Trends — Forecast to 2026”, https://www.databridgemarketresearch.com/reports/global-fertility-services-market.

3 Melissa Okey, “Mediocrity,” In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (blog), February 17, 2016, https://melissaokey.wordpress.com/2016/02/17/mediocrity/.

I collaborated with Melissa on a short film based on her blog, which we shot in the summer of 2019.

4 “Key Statistics from the National Survey of Family Growth — I Listing”, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed March 27, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/i_2015-2017.htm.

The terms “primary and secondary infertility” are from Greil 2011.

5 Faith Salie interview, “Having Faith in Your Eggs,” Eggology Club Podcast (01.13), November 8, 2017, https://eggologyclub.com/season-01-episode-13/.

6 Melissa Okey, “Pins and Needles,” In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (blog), January 17, 2016, https://melissaokey.wordpress.com/2016/01/17/pins-and-needles/.

7 Ronner and Marsh describe the difference between the Women’s Hospital that Sims founded and his and his colleagues’ private practices catering to wealthy patients. The physicians promoted the successes at the former in order to build up the latter, implying that procedures such as cervical amputations or cervical incisions were tested and perfected first on the population at the Women’s Hospital.

8 “Although John Rock was arguably one of the most skilled and successful practitioners of the surgery known as tuboplasty — the reconstruction of damaged fallopian tubes — his success rates remained very low.” (Marsh and Ronner 1996, 170). Rock eventually turned instead to his successful, pioneering research with Miriam Menkin into IVF.

9 See www.sart.org.

10 For example, the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (FCSRCA), mandating data self-reporting by clinics in order for consumers to evaluate their choices. Yet there is no penalty for non-reporting. And federally-funded embryo research that destroys the embryo is prohibited by the Dickey-Wicker amendment, first introduced in 1995 — privately-funded research is allowed.

11 IUI (intrauterine insemination) is a procedure in which washed sperm is placed directly in the uterus around the time of ovulation. IVF (in vitro fertilization) is a procedure in which an egg is harvested, egg fertilization takes place outside the body, the embryo is monitored for 5 days, and acceptably viable embryos are implanted in the recipient’s uterus.

12 One exception I found was Lita Linzer Schwartz’s Alternatives to Infertility: Is Surrogacy the Answer? (1991). Schwartz is a psychology professor and stresses the need for therapists to understand the psychological impact of ART processes on those undergoing treatment.

13 Melissa Okey, “Always bet on progesterone,” In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (blog), June 23, 2016, https://melissaokey.wordpress.com/2016/06/23/always-bet-on-progesterone/.

14 Cohen quoted in Faircloth, Kelly, “The Origin Story Behind the Annoying Term ‘The Biological Clock’,” Jezebel.com, May 25, 2016, Accessed March 30, 2020, https://pictorial.jezebel.com/the-origin-story-behind-that-annoying-term-the-biologi-1778741774. Faircloth is quoting from Moira Weigel’s 2016 book Labor of Love: the Invention of Dating.

15 Newsweek retracted the article in its June 4, 2016 issue. https://www.newsweek.com/marriage-numbers-110797. They’ve removed the original article from the internet.

16 Molly Hawkey is also an actor in the short film I made with Melissa Okey.

17 https://www.fertilityiq.com/topics/ivf/the-fertilityiq-family-builder-workplace-index-2019-2020

18 https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/stephaniemlee/tech-companies-fertility-benefits

19 Melissa Okey, “Go Home,” In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (Blog), January 28, 2016, https://melissaokey.wordpress.com/2016/01/28/go-home/.

20 For example, Life IVF Center in Los Angeles promotes monthly free seminars in which they raffle off a free IVF treatment (as discussed by founder Dr Frank Yelian on the February 18, 2020 episode of the Spermcast podcast). Another clinic discounts treatment when multiple patients share unused embryos.

21 Melissa Okey, “Back to Reality,” In Search of the Elusive Pink Line (Blog), August 3, 2016, https://melissaokey.wordpress.com/2016/08/03/back-to-reality/.